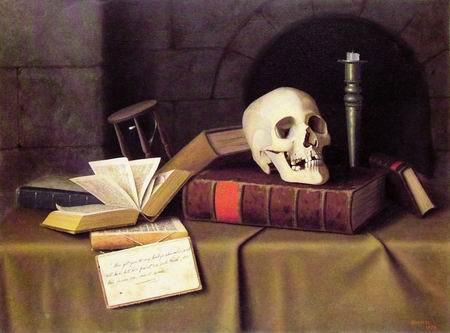

Memento Mori, “To This Favour,” 1879

Oil on canvas

William Michael Harnett

(American, born Ireland, 1848-1892)The Latin Term memento mori describes a traditional subject in art that addresses mortality. In Harnett’s example, the extinguished candle, spent hourglass, and skull symbolize death. A quote from William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, inscribed on the inside cover of a tattered book, reinforces the theme. It comes from the play’s famed graveyard scene, where Hamlet discovers a skull and grimly ponders his beloved Ophelia, ironically unaware that she is already dead. The “paint” in the quote not only refers to Ophelia’s make-up, but also wittily evokes the artifice of Harnett’s picture.

Mr. and Mrs. William H Marlatt Fund 1965.235

(The Cleveland Museum of Art)

While most still life paintings offer no narrative in their imagery, this does not mean there is no meaning to the piece. The meaning of this work by William Michael Harnett is offered directly in the title: Memento Mori, “To This Favour”. Even viewers not familiar with the Latin phrase memento mori can suss its meaning when viewing Harnett’s painting. An empty hourglass, a burned candled, and a skull are all icons of passing on, giving rise to feelings of one’s own mortality. As the phrase translated states, “Remember, you must die,” and so the viewer does. However, the meaning of this memento mori goes beyond that simple phrase.

“To This Favour” is a predominately dark piece, both visually and thematically, drawing the viewers attention to specific iconography with the touches of whiteness. The largest body of light color is the pages of the open books on the left. Harnett is known for his style of trompe l’oeil; in this instance he tricking the viewer’s eye into thinking one of the open books is motion. The upper of the two open books has three pages splayed in a position that would be impossible to capture in a still life painting if it were actually in motion. Each of these three pages curves in the exact manner one would expect it to do if it were falling under its own weight after being turned and left to fall to the opposite side of the book. Such is the trick, the tromp l’oeil, that the eye thinks the image so real that the page would fall at any moment. The book itself shows no meaning of death. The viewer cannot see the title nor read the text within it. Rather than be a symbol of the permanency of dying, the book, being half-open and in motion, may be a symbol of life: a life life half-over and passing quickly to the end.

The lower book is open as well, though its cover is torn from the binding. The aged, damaged book cover hangs over the edge of the table by a thread as if it, soon shall die. The inside cover is the closest object in the painting to the viewer, demanding one’s attention to the quote it bears. From Shakespeare’s Hamlet on the subject of death, the inscription reads: “Now get you to my lady’s chamber, and tell her, let her paint an inch thick, to this favour she must come.” In the play, the paint is Ophelia’s make-up; in this piece, the paint is the oils used by Harnett. Both paints are applied with thoughts death, which may have prompted the artist to use this particular quote. As one may know, Ophelia is already dead at the time the line is spoken by Hamlet, further compounding on the theme of death in the painting.

The next largest collection of whiteness is the skull, quintessentially the most recognizable symbol of death. The skull, like the book, is aged and damaged. It lacks several teeth and is a dirty, off-white color. Unlike the book, the skull faces to the side. The skull looks to the right of the viewer, whereas the book’s cover opens to the viewer directly. This positioning by Harnett aids in drawing the eye to the quoted text for which the painting is titled. The skull rests atop yet another book, this one much thicker and less damaged than the first two. The spine shows it to be a collection of Shakespeare’s Tragedies, which, like the thoughts this painting is meant to provoke, is full of death, loss, and mourning.

Another obvious symbol of passing used by Harnett is the extinguished candle. Light entering the scene from the left side of the painting creates a reflection on the candlestick. A broken line of white draws the viewer beyond the darkness of the whole piece to the candle. On the table, it sits behind the skull-topped book. Behind the candlestick and skull is naught but a darkened archway; a light-less passage through which the used-up candle cannot guide the viewer. Even the off-painting light source cannot guide the viewer’s eyes to what lies within that hall. It creates a sense of anxiety and anticipation at the thought of the great beyond. One cannot see what is through the passage, just as one cannot know what is seen after death.

Behind the open books sits an empty hourglass, presumably the sand has run out to the bottom though it is not seen in the painting. It is yet another iconic reminder of one’s own mortality and the passage of time. It is tilted in a slightly unsettling way and is perhaps propped up by one of the other books behind the open pair. Like the open book before it, the hourglass appears to be at the cusp of motion. It appears ready to fall, or even already falling, in its tipped position. The only portion of the glass seen is that which reflects the light from the left. The lighting effect may be Harnett’s real reason for presenting the hourglass at an angle. The glass is so clean that the viewer can see to the stone wall beyond and, had the hourglass not been positioned as it is, the reflected light may have been too much or too little. Too little, and the hourglass would go unnoticed. Too much and it would detract from the whiteness of the book cover and detract from the intended focus.

The books surrounding the hourglass have no visible titles, though they appear to be at different stages of aging. One book, positioned at an angle on the left side of the Shakespeare tome, has a few pages that seem to be shifted and poking out of the rest. This can be read as a well-used book that is possibly near “death,” though not as near as the book with quote upon it is. A book lays flat to the left of the hourglass and the open books. It appears to be smooth and not at all damaged, though perhaps a bit dusty. The sixth and final book is perhaps in the same stage of life: its pages are neat and straight, but are yellowed from age.

The table upon which this memento mori still life is placed is a drab, olive-brown. It does not shine like the silk painted by other artists using oils, but it is as smooth. It seems to be very plain, which could be indicative of it being over-used and near its end along with the books and candle. The lack of luster in the cloth, as well as the rest of the objects, shows death to be very mundane and common. This fits with the sense of tragedy in Hamlet as no death in the play is glorious, no one died a martyr, and celebrated at another’s death.

Still life paintings are oft devoid of deep meaning. However, William M. Harnett’s Memento Mori, “To This Favor” bears a rich subtext of the commonality of aging and loss in addition to it’s obvious subject of death. Each object is positioned to relate to the other as aging, death, and anxiety all relate to each other. Harnett’s work reminds one of one’s own mortality as intended, but also reminds us that those we love will pass, too.